Through the end of the regular season, Florida averaged 31.8 points per game. Is that good?

I have a few ways of trying to answer that question.

Recent program history

The best offensive architect that UF has had since Steve Spurrier left is Dan Mullen, and it’s not close. The only other candidate — keeping in mind that Urban Meyer didn’t directly run offenses, and his attacks’ effectiveness at both Florida and Ohio State ebbed and flowed with his coordinators — is Larry Fedora. He was only play caller for one year, though, when the Gators averaged 31.8 points per game in 2004. But, he did go on to lead some high powered offenses as OC at Oklahoma State and as head coach at Southern Miss and UNC.

Mullen is the only play caller to surpass that 31.8 PPG level at Florida since 2002 aside from Steve Addazio in 2009 (35.9 PPG) The Divemaster had a cheat code that year since he got to have senior-year Tim Tebow behind center. The scoring dipped below 30 per game in Addazio’s final year as OC in 2010. Mullen went over that mark five times, from 2007-08 and from 2018-20.

UF still has a bowl game to go this year. If the Gators put up 32 or more points, the 2022 team will be the highest scoring post-Spurrier team that didn’t have Mullen or Tebow. That’s not bad for having a very inconsistent quarterback, little playmaking ability at receiver outside of maybe Ricky Pearsall, and a lackluster tight end position outside of Keon Zipperer (who missed the final month to injury).

Even if they don’t hit 32 and fall short of the ’04 team’s output, it’s still worth noting what that earlier team had: sophomore Chris Leak in an offense that suited his skills, Ciatrick Fason going for more than 1200 yards, and a receiving corps with O.J. Small, Chad Jackson, Bubba Caldwell, and Dallas Baker. That’s a better spread than what this year’s team had to work with.

National comparison

College football is a lot different in 2022 than in 2004. Scoring and tempo are both up, the spread revolution that was just beginning in ’04 ate the sport, and the 12th regular season game (instituted for good in 2006) largely ended up giving teams an extra cupcake game to run up the score in.

When the ’04 team averaged 31.8 PPG, it was 19th in the country. This year? As of today, the Gators tied for 43rd.

From 2002 on, the lowest national average of points per game for FBS teams was 24.4 in 2006. You may remember, though, that the NCAA test drove some new clock rules to speed the game up that season. They worked a little too well, and you can see it in the scoring average. The rule makers scaled them back immediately, though, so that was the only season with an average that low.

That season aside, scoring averages ranged from a low of 26.6 PPG in 2004 to 28.4 in 2007 between 2002 and 2009. In 2010, the scoring average hit 28 PPG for good (exactly 28.0 that year), and it hasn’t been below it since. Scoring actually peaked at 30.0 in 2016 and was last above 29 PPG in 2018. Still, it’s been between 28 and 29 since then.

The Florida teams that beat the national average the most were 2008 (16.4 PPG, or 60.4% above average), 2007 (14.1, or 49.6%), and 2020 (11.0, or 38.1%). The eight best teams at beating the national average, both in raw points and percentage of the average, came in either 2004 or the stretches from 2006-09 and 2018-20. Yes, even the ’06 team with its seemingly modest 29.7 PPG rates highly here because of how much those clock rules knocked the average down.

The 2022 team right now, before the Championship Week games, is in ninth place among these teams. They’re 3.4 points per game above the national average, or 12.0% above it. The only other post-Spurrier team to get to double-digit percentage points was 2003, and the other teams to at least be above the average were (in descending order) 2021, 2010, 2005, and 2014.

In other words, the ’22 team’s scoring rate was a healthy bit above average for the country but not elite. You have to go back to 2009 Alabama (32.1 PPG) to find a national title winner with a scoring average in the neighborhood of this year’s UF team, and every champ since 2012 has averaged more than 35 PPG. You have to have a crushingly good defense to win with a scoring output at this level.

Speaking of…

Adequacy given the defense

Back in December 2017, I wrote a piece suggesting as gently as possible that Florida could not win a national championship with Todd Grantham as defensive coordinator. Gently, because he’d just been hired and few people want to read something raining on the parade that quickly.

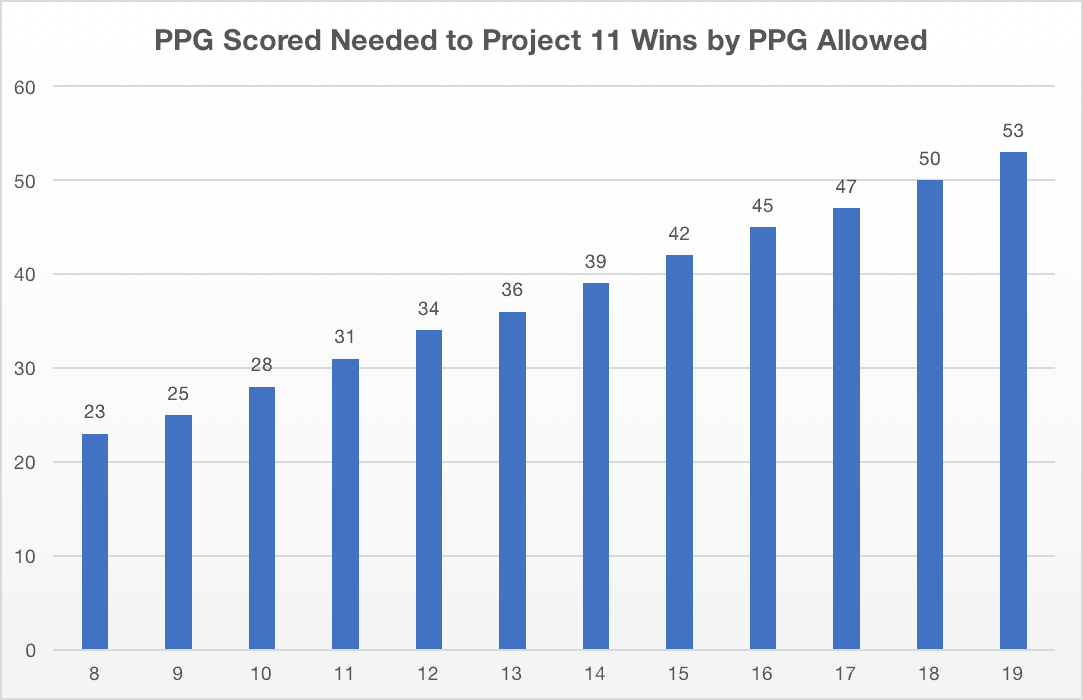

You can hit that link if you want the details, but I used a standard formula in the analytics world to make this chart. If you look at the points per game allowed levels on the bottom, the bars tell you how many points per game the offense has to score to expect an 11-1 regular season record without relying on good luck. I picked 11-1 because you typically can’t make the four-team College Football Playoff without at least finishing with that record. Things will change with the 12-team format in 2024, of course.

You can also work it the opposite way and look for an offensive scoring level and trace it down to how many points a team can allow and still expect 11-1. For 31 points per game scored, you can only allow 11 points per game to get a luck-free shot at a one-loss season. Eyeballing it — the figures here are slightly rounded anyway — and at 32 points per game like the ’22 team basically has scored, you get all of 11.3 points per game allowed to work with.

This year’s team allowed, well, a lot more than 11.3 points per game. They gave up 28.8 PPG, which is far beyond the bounds of the chart. I calculated it out for a laugh, and you’d need to score 79.3 PPG to drag a defense that allows 28.8 PPG to a luck-free 11-1 finish.

This piece is about scoring and not points allowed, so I won’t digress on the defense except to say that it has to get a lot better.

In non-garbage time drives, UF was actually 30th in points per drive per Brian Fremeau. Simply getting more drives per game would help the team score more points, and the combination of a quicker pace and more/faster defensive stops would help there.

Another piece of low hanging fruit is red zone scoring. The Gators are 117th in score percentage, between UAB and Colorado. UF is middle-of-the-pack nationally at 65th with a 62% touchdown rate, but the field goal rate is very low at 14%. Adam Mihalek was 8-of-10 on field goals under 40 yards, so the low field goal rate is more due to going for it on fourth down a lot than having a lot of errant kicks. Regardless, punching it into the end zone from close range would help a lot too.

Championship teams of late have tended to score more than 37 points a game, and most have been above 40. Getting there would afford the defense some more margin for error, but the fewest points per game a Florida team has allowed since Charlie Strong left has been 14.5 in 2012 and 15.5 in 2019. It’s not a requirement to get that low, as 2016 Clemson, 2019 LSU, and 2020 Alabama all won national titles while allowing 18 points per game or more. The ’16 Tigers even missed 40 PPG scored (though they got close at 39.2 per game) while allowing 18 PPG, and they still went 14-1.

The chart above isn’t an iron rule, just a rule of thumb about how fortunate you want to have to be. The formula I’m using said 2016 Clemson probably should’ve gone 13-2 across 15 games, and in fact seven of their 14 wins were by one score or less. Florida doesn’t have to get to 39 points per game scored and 14 allowed to be able to finish 11-1, but it’d be a better idea to hit those metrics than not.

This factor is entirely contingent on how good the defense can become, and that’s a complete mystery for now.

What I can say is that Billy Napier’s first season running an offense in Gainesville turned out better than more than half of the post-Spurrier teams scoring-wise. Most of the teams that beat this one out had either Mullen, Tebow, or both. The only other team really to surpass it was one with Fedora calling plays, and he was very good in his own right until things collapsed in his final two seasons in Chapel Hill.

It wasn’t a blowout performance, but it was easily solid at worst. Napier will need to do a lot of portal work this winter to keep the momentum going, but he has a number of highly rated offensive recruits on the hook and ready to sign. The 2022 offense will probably be either the least or second-least talented unit he works with, depending on how the portal haul for next year goes, so it’s not unreasonable to expect things to for sure be better from 2024 on.