The question of what has gone wrong with the Florida defense of late is one with too many answers for a single article. The fact remains, though, that 2019 was the last time UF had a good defense, and as of this fall that’ll be five years ago.

One way to simplify things is to break down defense into two categories: efficiency and explosiveness. Efficiency is about how good the defense is on a down-to-down basis. Explosiveness is about how often a defense allows big plays and how big those plays are when they happen.

The measures of these that I’ll be using are success rate for efficiency and expected points added on success plays for explosiveness. Let’s take a quick moment to define what those are so we’re on the same page. I’m using figures from College Football Data, by the way.

Success rate is the percentage of total plays that are deemed a “success”. To be a success, a play has to gain at least 50% of the yards to go on 1st down, at least 70% of the subsequent yards to go on 2nd down, and 100% of the yards to go on 3rd or 4th down. This is a standard definition that’s been around a while, and I made a video explaining it the better part of a decade ago if you want to watch something quick about it.

Success rate is not perfect, but it is widely used because it’s better than a lot of alternatives. For instance, it gives a team credit for gaining two yards on 3rd & 1 while penalizing a team for gaining eight yards on 3rd & 15. It does have a drawback that it can’t account for when a coach decides to use four-down logic, which is when he doesn’t try to convert on 3rd down but rather wants to advance the ball enough to make 4th down easier. Billy Napier likes to use four-down logic, but he probably doesn’t do it enough to move the numbers much for a whole season.

The explosiveness measure is average expected points added (EPA) on plays that are a success by as determined by success rate. The idea of EPA is basically that the way to score is by gaining yards, and yards near the opponent’s end zone are more valuable than those far away. It assigns point values to yards and figures out how many theoretical points a play gains. A ten-yard gain from the opponent’s 20-yard-line will yield more EPA than a ten-yard gain from the offense’s own 20.

If you didn’t want to read all that: defenses need to be consistently good on a down-by-down basis, not give up too many big plays, and not give up extremely long big plays when they do inevitably allow them. You want to see lower numbers for both the efficiency measure (success rate) and the explosiveness measure.

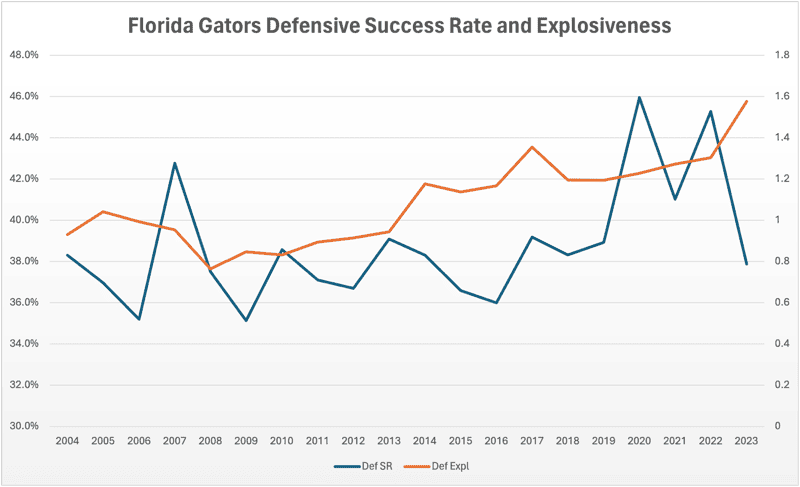

To get a good perspective, I found Florida’s defensive success rate and explosiveness for the last 20 seasons. I chose the option to eliminate garbage time, which is when the scoring margin is more than 38 points in the second quarter, more than 28 points in the third, or more than 22 in the fourth. That tosses out a lot of bad data.

The blue line is efficiency/success rate plotted against the left Y-axis — note that it doesn’t start at 0% to make things easier to see — and the orange line is explosiveness plotted against the right Y-axis.

Florida used to keep success rate consistently below 40%, which is good since 42-43% is around the national average in a given year. There was one blip in 2007, but otherwise things were looking good. Then in 2020, success rate shot way up for three years.

The explosiveness line is perhaps more interesting. It hit a low in 2008 and has risen steadily since then. That covers times when both proven defensive minds (Muschamp, Collins) and, uh, other defensive minds (Grantham, Toney, Armstrong) were in charge. Offenses have had the upper hand in the spread era, with things like RPOs exploiting the college illegal-man-downfield loophole and high tempo attacks leading to more big plays in general.

It’s very easy to tell from this chart what went right and what went wrong last year. The non-garbage time success rate allowed plummeted to 37.9%, the lowest figure since 2016’s 36.0%. It’s not down to a Charlie Strong-era performance, but that was more than respectable.

At the same time, the explosiveness measure shot through the roof to a new high of 1.58. Similarly bad one-year jumps could also be seen going from 2013 to ’14 and 2016 to ’17, albeit starting from lower baselines, so it’s not unprecedented. It’s not even completely off the trend line — which, to be clear, is a distressing trend line. However, it’s noticeably worse than LSU’s 1.38, and Brian Kelly fired nearly his whole defensive staff after the season. It’s also worse than USC’s 1.35, which got their DC fired as well. There is no way to sugarcoat that number.

I am not the first person to point out the divergence between the efficiency and explosiveness defense last year. I believe the Gator Nation Football Podcast hosts were the first ones I heard beating that drum, and others have picked it up since.

What I’m trying to add here is an illustration of how I think that insight is worth highlighting. The success rate allowed by the 2023 defense was in line with many past defenses that Gator fans approved of. The explosiveness allowed, however, was stunningly high.

The best hope is that the high explosiveness allowed was a function of youth, as UF would sometimes have as many as four or five true freshmen on the field at once on defense. All those guys have valuable experience now, plus they’ll have another spring practice session, another summer of playbook study, and another preseason camp under their belts by Week 1.

There are personnel reasons to think there could be improvement as well. The near-complete lack of pass rush resulting from Justus Boone’s preseason injury meant that quarterbacks had time to shop the field when they wanted to make a big play. Don’t discount this point: the defense allowed a mere 28% success rate on passing downs (2nd & 7 or more, 3rd/4th & 5 or more) but a catastrophic average 1.82 EPA on those relatively few success plays. Fortunately, the edges this year have a lot more depth.

The linebacking corps also struggled mightily after Shemar James went down. Transfer Grayson Howard and signee Myles Graham bring physicality and skill that simply didn’t exist outside of James last year.

Finally, perhaps the wisdom of experience that Ron Roberts brings will help get that explosiveness figure back down. Austin Armstrong called for the right thing a lot of the time, as evidenced by the success rate numbers. It’s just that when he was wrong, he was really wrong and too often in critical spots.

If Florida can keep the success rate where it was last year, the defense will be in such good shape if it can just stop breaking down so badly, so often. Even if they have to give up a percentage point or two of success rate to cut down on the big plays, their performance last year in efficiency was good enough that they can afford to make that tradeoff.

It wasn’t all bad last year, but the bad so drastically outweighed the good that it made the good hard to see. I hope that now you can see where the good was, even as the staff has a hard road ahead to get the explosiveness factor back down to acceptable levels.