Breathe, Gator Nation. It’s going to be ok. Kentucky actually has decent talent this year, and is being coached up by one of the Stoops brothers. They’re going to give a few teams trouble this year, even if it doesn’t reflect in their record. On the flip side, it’s worth noting that most of our problems on Saturday were self-inflicted. Between the drops on third down, missed assignments in pass protection, dropped interceptions, and overthrown deep balls, there were plenty of mistakes to go around. The positive thing, though, is that these mistakes were executional in nature, meaning we were not getting beat on talent as was the case last year at several positions on the O-Line and elsewhere as the injuries piled up. The other thing really positive that can be taken from this game is that we had receivers running wide open all night. Looking at the film, the reason for that is actually one of geometry: Triangles.

Let’s take a trip back for some history, in particular about a guy named Sid Gillman. Gillman is generally credited as being the father of the passing game. He figured out that by distributing and timing routes properly horizontally and vertically and including man beaters with 5 receiving targets, that zone defenses could not defend the play despite superior numbers. It’s basically how the passing game still works today and is the foundation for pretty much all of the theory behind route concepts. Take a look at Gillman’s coaching tree and you’ll see pretty much a who’s who of the NFL hall of fame.

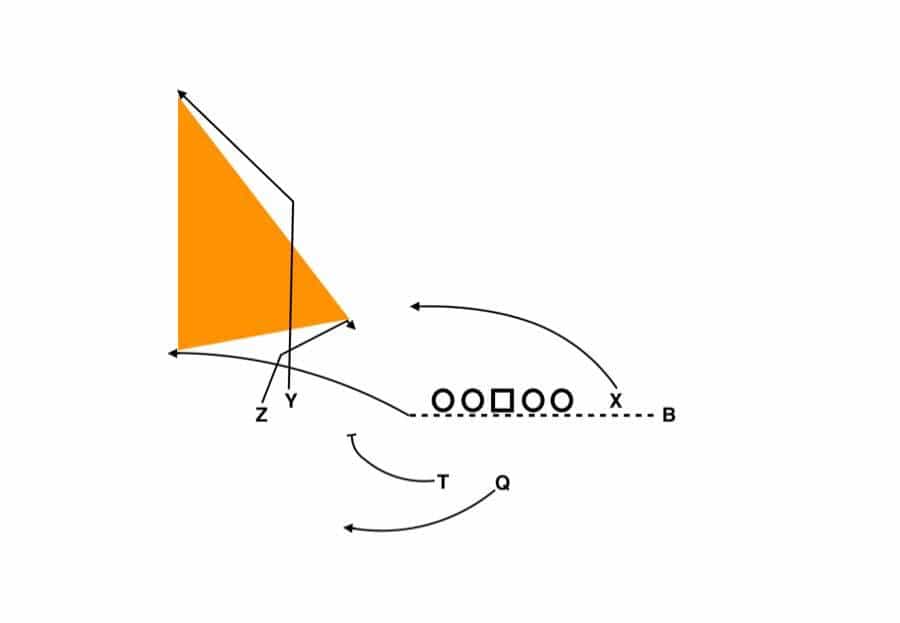

One of the coaches in his tree was Bill Walsh. Walsh gets a lot of credit for the West Coast offense, and one of the innovations that he spun off of Gillman’s theory was this idea of combining vertical and horizontal stretches in an area of the field. Walsh further combined these stretches with a man-beating concept into a single read. This is what we know today as the triangle stretch. Pretty much all of the newer passing concepts in the game today are what we call triangle stretches.

The reason why they are so popular is because of how effective and versatile they are against a variety of coverages. Against cover 3, sending all 5 receivers on properly spaced curls is more effective, as is a 3-level flood play against cover 2. However, the problem comes in that coaches can rarely predict these days what kind of coverage their offense will face. Even post snap, it can be difficult for even top NFL quarterbacks to diagnose exactly what the coverage is due to the increased use of combination coverages, disguises, and rotations. Thus, triangle reads are one of the most valuable tools in an offensive coordinator’s toolbox. Let’s look, for example, at the play Kurt Roper called in the second overtime against Kentucky that resulted in an incompletion intended for Demarcus Robinson in the flat.

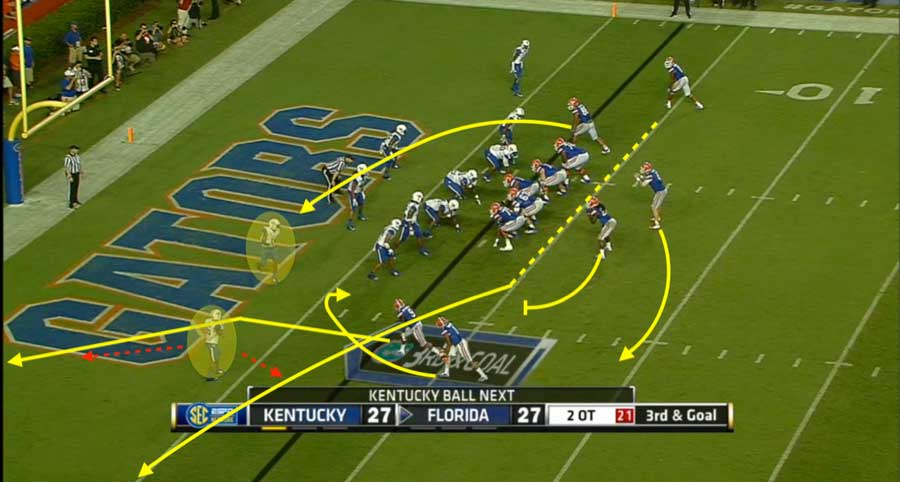

The play essentially combines a smash concept stretching the corner on the outside with the corner/flat combo of Pittman and Robinson along with a horizontal stretch of the with the snag/flat combo of Dunbar and Robinson stressing the flat defender. Roper then uses motion to create a rub in hopes of picking off man defenders.

In concept, it’s fairly similar to the Mesh play I showcased last week, and not coincidentally Snag has become part of the core Air Raid playbook also. It’s a rhythm throw designed to come out by the end of a 5 step drop, and is often thrown out of a 3 step drop. The difference lies in how it is read by the quarterback. Whereas Mesh has a deep to shallow progression, Snag is usually read by looking at a pair of defensive keys: the corner and the next man inside.

Driskel first has to look at the corner. If the corner stays up, as in cover 2, he’ll throw the corner, with the responsibility of “throwing his receiver open.” If the corner drops, as in cover 0, 1, 3, or 4, Driskel will move on to the snag flat combination by reading the next man inside. In this case, the corner drops to the flag route.

If the next man inside stays in to take the curl, he’ll look to the flat. If he vacates, the curl should come open.

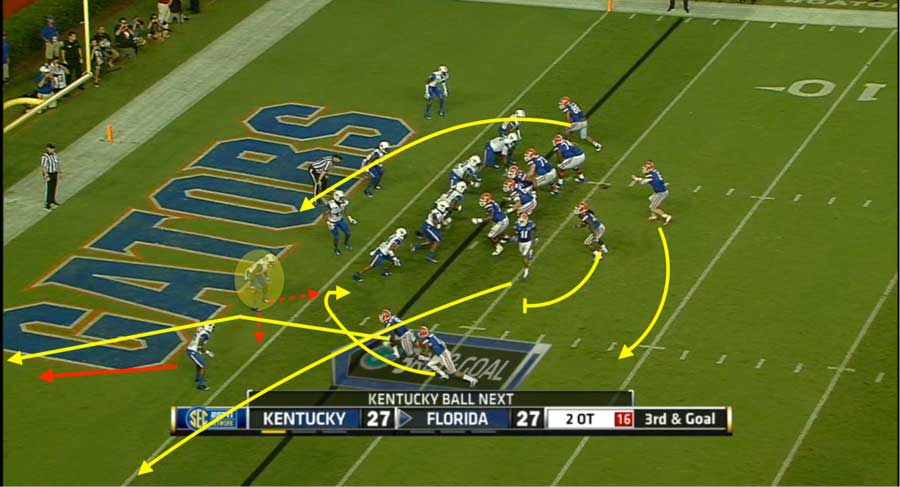

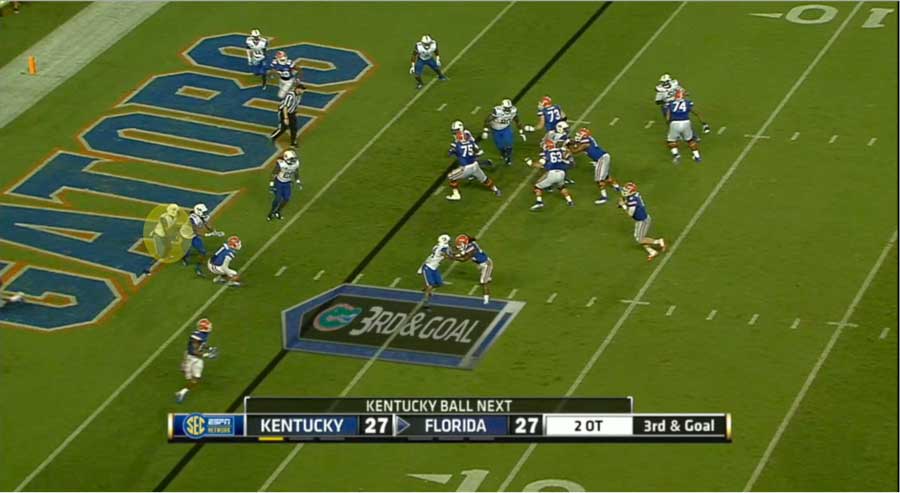

In this case, he stays inside, the rub works, and Robinson comes wide open for what should have been an easy completion. Driskel, however, is perhaps too focused on making sure he threw to a receiver across the goal line, is late in going to Robinson, allowing the corner to come back up and causing Robinson to run out of room.

It was one of several executional errors on the night, however the important thing to take away is that Roper’s scheme works and that it wasn’t a matter of us being overmatched by a much-improved UK team.

Not by coincidence, this exact Snag concept was the play the Steelers used to win Superbowl XLIII against the Cardinals.

It goes to show you how coaches of every level will reach for these triangle concepts in the most crucial of situations. Kurt Roper has certainly shown us a healthy dose of triangles in his first two games here at Florida, and I only expect that to increase as the Gators approach the meat of their SEC schedule, beginning this week with Alabama. Given Kirby Smart and Nick Saban’s propensity to disguise their coverages and send pressure, triangle stretches will be crucial for getting the ball out to Gator playmakers with room to run.

This breakdown is really helpful. At first I thought that Jones engaging in his block may have been in Driskel’s throwing lane to Robinson and he feared a deflection/INT in the end zone in OT. However, in that one still, you can see him looking towards the corner of the end zone for possibly a split second too long.

I think he was looking at Dunbar rather than the corner, waiting for Dunbar to work back outside, as the snag can actually turn into a pivot. The corner was playing outside leverage and bailing at the snap, so there was no reason Driskel would still have been looking his way.