College football experienced its second-largest per-game attendance drop ever in 2017. The SEC experienced the largest drop among Power 5 conferences. Looking at the details, it’s not hard to figure out why the conference had a down year at the turnstiles.

Ole Miss, playing under a bowl ban for an interim head coach, saw its attendance fall nearly 6,300 per game. Arkansas fell by slightly more, while Tennessee slid about 5,200 per game; both were in the final years of underperforming coaches. Texas A&M fired its less-underperforming coach after 2017; it was down around 3,100. LSU fans, unimpressed by the Ed Orgeron hire, showed up about 2,700 lighter than in 2016. Only Kentucky and South Carolina, happy to be coming off of bowl bids, saw appreciably higher attendance.

Florida had a modest drop in attendance, as its average crowd declined by 1,131 per game over 2016. The relative number isn’t so surprising given the 4-7 finish versus the prior year’s nine-win, division-topping campaign.

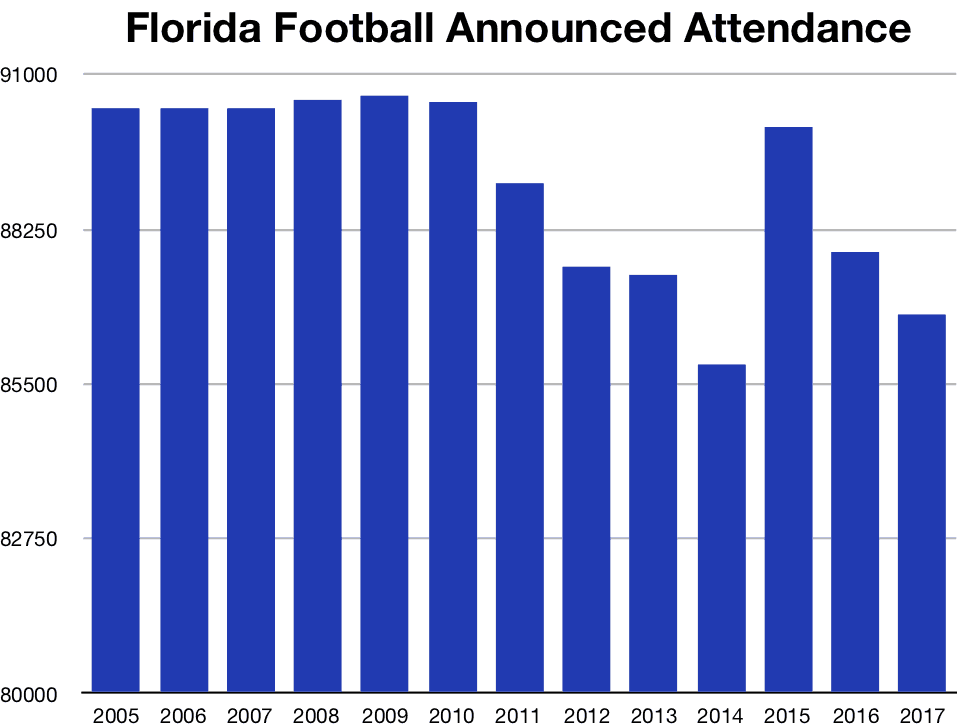

What’s more notable is that the 2017 season had the second-lowest attendance at UF since the expansion of the Swamp in 2003. An average of 86,715 people showed up to Gator home games last year, besting only 2014’s mark of 85,834 per game.

Falling attendance is not only a problem in seasons that include a coach being fired. I’ll show you the attendance in every year since 2005, and you tell me when the trouble began.

Gator fans weren’t impressed by the last two coaching hires. The 2011 season was the first — with a caveat — since the 2003 expansion to have an average attendance below 90,000. It’s only broken that level once since.

The caveat is that 2004 technically had an average attendance of 88,409. That too was a year in which a coach was fired, so it’d be logical to chalk the drop up to that. It’s not the problem, though. The hurricane-rescheduled Middle Tennessee game officially had only 80,018 people at it, the lowest announced attendance of any game since ’03. If you remove that game, the average attendance for the season was 90,087 — low for the time, but still above every one of the Will Muschamp and Jim McElwain years.

In fact, the 2004 South Carolina game is instructive in this sense. It came after Ron Zook was fired and the season was lost, and it was before Steve Spurrier became a draw for UF fans to care about the Gamecocks. Despite those factors, the game still had 90,294 people show up for it.

The South Carolina game in 2014 that came after Muschamp’s firing was a different story. Only 85,088 people showed up for it. The 2017 season didn’t have a non-FSU home game after Mac’s firing, but the UAB home game only drew 84,649.

I don’t know if attendance factored into McElwain’s ouster, but it certainly didn’t help. Two of the five lowest-attended SEC home games since the 2003 season came in 2017: the lowest, Vanderbilt (84,478), and the fourth-lowest, Texas A&M (86,114). If fans won’t even show up well for conference games, the head coach has lost the base.

The writing on the wall for Muschamp came earlier in the slate. Home openers tend to be well-attended since they’re the first chance for excited fans to see the team, but the three lowest-attended games besides that ’04 Middle Tennessee game, the 2017 UAB game, and contests against FCS opponents were the 2014 opener against Eastern Michigan (81,049), the 2013 opener against Toledo (83,604), and the 2012 opener against Bowling Green (84,704).

Speaking of those FCS games, Gator fans wouldn’t show up to the late-season contests against those lower division teams either. All four such games in the Muschamp era are likewise in the bottom ten of attendance since 2003.

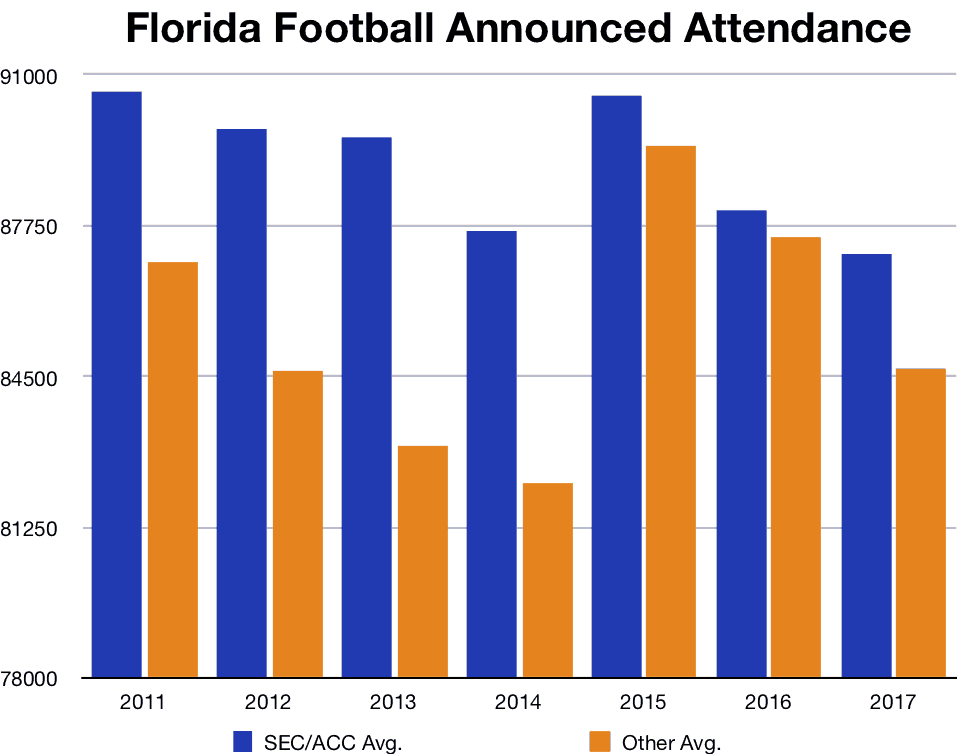

I can break out the games against SEC teams, FSU, and Miami versus the cupcakes for you. There’s not much point in doing so prior to 2010, as in that time the difference in averages was never more than 500.

Interest in those cupcake games is dwindling. They still serve a purpose, as they’re easy money for the athletic department and provide a less-intense environment for fans with small children to bring their little ones to the game. However, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that UF has begun signing up for neutral site games like the Michigan game last year or playing Miami in Orlando in 2019. UF doesn’t want to take the revenue hit of a true home-and-home when a neutral site will pay as well as a home game does, and they become more attractive when a MAC or Sun Belt team playing in Gainesville could result in 5,000 or more empty seats.

Scott Stricklin talked about improvements to the Swamp earlier this month, and one possibility he mentioned was actually reducing the capacity by replacing bleachers with chairs.

With a few exceptions like AT&T Stadium where the Dallas Cowboys play, it’s been a trend for years in pro sports to reduce capacity in renovated or replacement stadiums. Attendance is basically down in all sports, so why not make it nicer for the ones who do come than keep stuffing them in to save empty bleacher spots elsewhere? Believe me, Stricklin has a better insight into all of this. He has the real numbers; college football attendance figures tend to be inflated to some degree everywhere.

I do expect a bounce-back year for attendance in 2018 with Dan Mullen’s return. McElwain got a first-year bump, as 2015 is the only season since 2011 with an average attendance above 90,000. The highest announced attendance since the stadium expansion was the Florida State game of that year.

If Mullen wins big, or at least at first provides a fun and exciting product, the fans will come back. If he doesn’t, there’s no reason to think the packed houses will last much longer than a year. Games are expensive in both time and money to attend and the TV experience is so good that no school can expect to pack the house merely by opening the gates anymore. The past seven seasons prove that UF is not immune to that fact.