What a week. Between the 4th quarter comeback win to make it 10 straight over the Vols, Will Muschamp’s fantastic post-game trolling of UT fans, and the shenanigans involving Treon Harris, and later Gerald Willis and Skyler Mornhinweg, it has been an eventful few days for Gator fans. Despite all of that, there is thankfully still football to be played, and thus X’s and O’s to discuss. Those X’s and O’s will, for better or worse, involve Jeff Driskel again, and thus it makes sense to look again at our offense with him behind center, particularly a play concept we’ve run several times over the last few games, with some mixed results.

This concept has been used by a variety of offensive coaches, from Bill Walsh with the West Coast Drive concept, to Lavell Edwards at BYU and later Hal Mumme and Mike Leach, to Mike Martz in the NFL with the Rams (as seen below) and Bears. This concept is the shallow cross, and it has been a staple of virtually every successful air attack over the last 20 years. It’s a concept that forces linebackers to make a full speed choice against a more athletic receiver running full speed across the field.

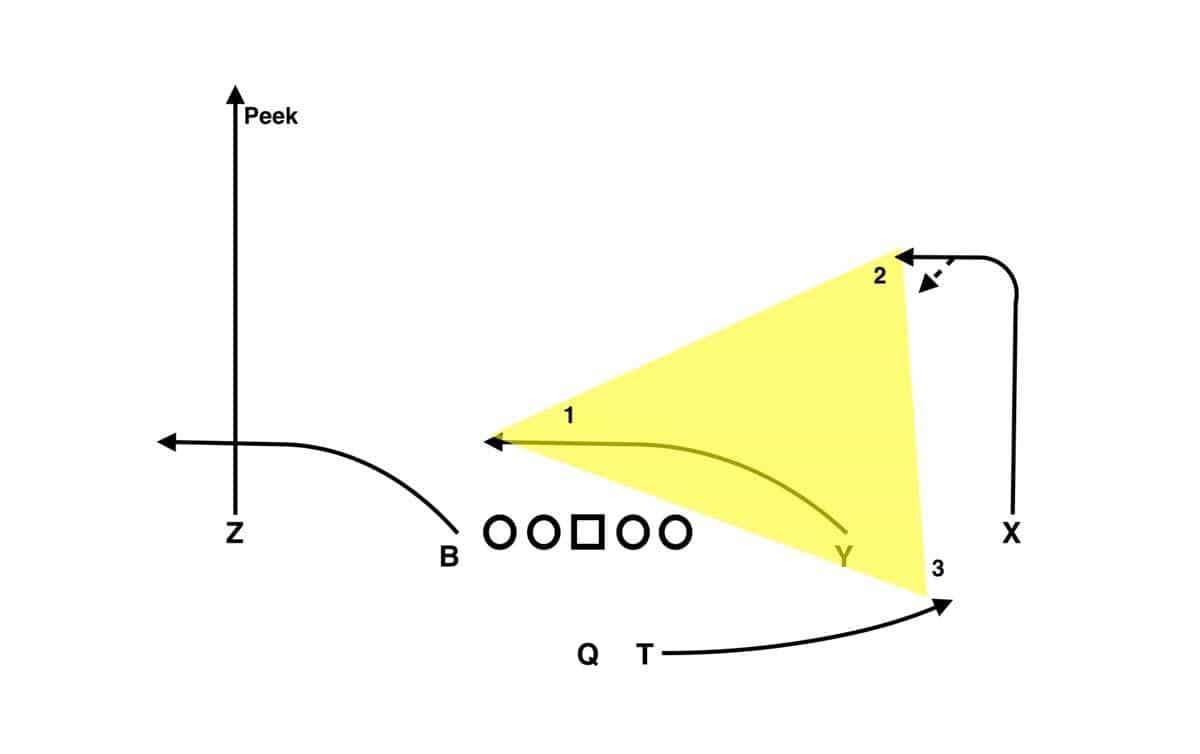

The shallow cross is typically combined with a flat route and some sort of inside breaking intermediate route. In the old Bill Walsh west coast offense, this was typically a dig run from the same side, with the shallow clearing for the dig and then progressing to the back in the flat as a checkdown. This gives you a triangle stretch to the strong side, and is paired with a 2-man combination to the weak side, with one of those routes being a flat route by the inside man. The flat and hot routes are built in hot reads that are thrown when the defense blitzes from either side or the middle.

One of the bigger proponents of the shallow cross has been Mark Richt, dating back to his time at FSU. It may be somewhat sacrilegious here on Gator Country, but Richt actually gave a pretty great overview of the concept a few years back at a coaching clinic that is worth the watch:

Note the play diagram behind Richt. One of Richt’s innovations was to turn the dig route into what he calls a choice route. Richt’s choice route allows his receiver to basically run a 12 yard curl working over the top of the curl defender or working inside and back to the quarterback, depending on whether or not the curl defender widens.

Roper’s version allows the receiver running behind the shallow to either run a dig or sit down on a deep curl, depending on how the defense is playing him to that side. If the defense is playing him inside and underneath to take away the curl, he’ll run the dig. If the defense widens or drops back, he’ll turn the speed cut of the dig into a curl and sit in the hole.

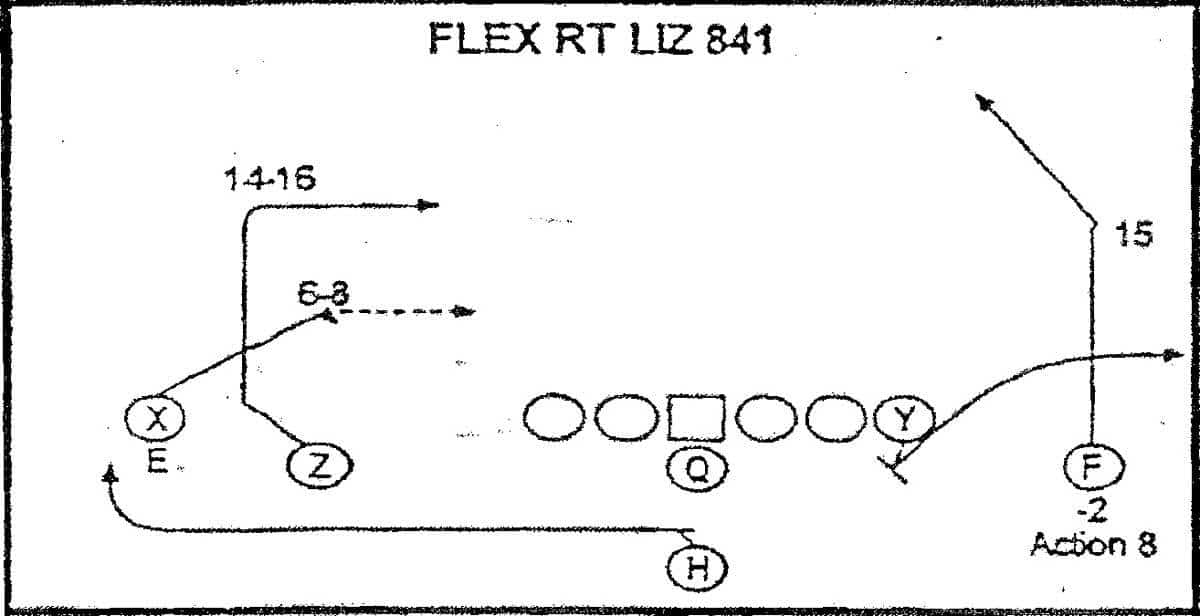

Roper’s real twist comes on the weakside combination. Whereas Richt almost always runs this with a slant/flat combination, Roper turns that slant into any number of deep or intermediate routes. This likely takes place through tagging the route in the play call instead a sight adjustment at the line. I’ve seen it with another dig route, a slant like Richt’s play, and an out route, but by far the favorite route to run with this combination is a go route. Often, this is treated as a peek or glance read, coming first in the progression before working to the shallow if the pre-snap look is favorable. If Jeff chooses to work this route, he’ll give it a quick glance and if the receiver doesn’t immediately get behind the corner, he’ll get back to the shallow before he’s at the end of this drop. If the corner is playing off or has help stacked over the top, Jeff won’t even work that combination. Drawn up, it looks something like this:

The idea is that the shallow will either come open or clear out the hook/curl defender for the dig/choice if they run with shallow, and either way you should have a receiver catching the ball coming out of their break and able to run without breaking stride if the pass is thrown on time. If neither are open, the checkdown should open up late and if not then the quarterback can either run or throw it away. It’s a simple play with a simple read that gives us a chance to eat chunks of yardage, and it is one that Jeff Driskel has thrown with a modicum of success. It is also versatile in that it can be run on any down and distance.

Like most of Roper’s passing plays, it’s not a hard play to teach or learn, but it provides multiple answers for various problems a defense might throw at a quarterback and also provides multiple stresses on an area of the field that makes it hard for a defense to reliably defend without cheating support from the Go route on the backside. The question will be whether Driskel and his receivers can capitalize on the opportunity when it is there against John Chavis and his fire zones and 2-deep zone dogs from his 3-2-6 Mustang package and standard 4-3 look. If he can’t, I expect he will have another rough afternoon. The good news is, LSU’s personnel defensively isn’t what it has been the last few years, so yards should be ripe for the taking if Jeff can just get the ball out on time and with accuracy and if the receivers can bring them in. If they can, the only thing we’ll all be smelling come Saturday night will be burned corndogs.

Well, you certainly know more about football complexity than I, BUT I have some experience with the language we share. When I see “.. it’s not a hard play to learn ..” in the same sentence with “.. multiple answers to various problems a defense might throw at a quarterback ..”, all I can say is that either the “other” plays must be calculus problems, or this isn’t all that easy to learn.

Combined with the likelihood that on some? many? most? plays somebody doesn’t get their assignment or execute it right, it isn’t so surprising that Jeff gets confused but rather shocking that another quarterback doesn’t. Maybe it is because they make it more simple for the less experienced QB.

Studies of how much information can be processed by military pilots under duress (smoke in cockpit, plane on fire, etc) contributed to the term “task saturation”. People have different saturation levels. When you might die if you don’t do the right thing, the number of decisions you can make at best is 2, sometimes 3. Also, sometimes it is zero.

Maybe they should try to make it as simple for Jeff as they do for the freshmen. Then maybe, just maybe, experience, success, confidence, trust could snowball into the kind of QB that Jeff otherwise has all the so-called tools to become. It could take years.

It’s simpler than you might think. It’s basically a pre-snap look to the side of the go. If that isn’t there, ignore that side and read the triangle timed with your drop.

The multiple answers part is necessary because the problems modern defenses present aren’t within the control of the offense, and comes in because the pattern actually has built in answers for blitzes from different locations with the flats and shallow. The simplicity is that the answer is the same no matter what the problem: throw where the blitz came from. It doesn’t change the pattern or what anyone else is doing, but it does allow the quarterback to have a panic button with no real read involved when he’s under duress. Granted, there are some things a defense can do to prevent that (i.e. dropping a lineman into a shallow zone and rushing a linebacker), but these are things you pick up on film in advance and develop alternate answers.

As compared to many offenses that require receivers to recognize and adjust their routes and be in complete sync with the quarterback, this is a relatively simple play. It’s one that I would bet even our freshmen are executing in practice. It’s really part of our bread and butter in the pass game, and is basic enough that it could be taught to high schoolers.